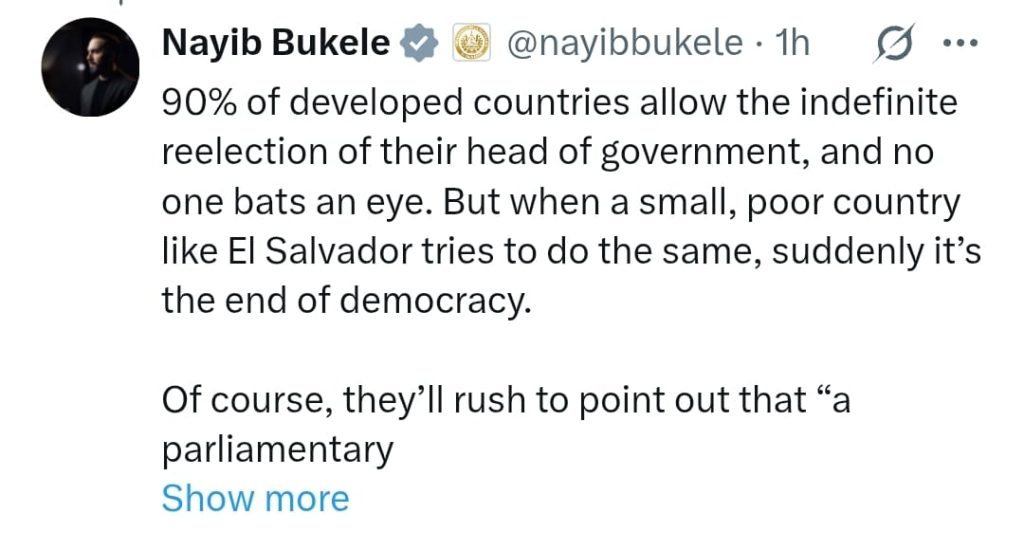

When El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele tweeted on August 3, 2025, that “90% of developed countries allow the indefinite reelection of their head of government and no one bats an eye,” he wasn’t just defending his political choices—he was exposing a deeper hypocrisy embedded in global power structures.

Bukele’s message wasn’t merely about electoral rules. It was a sharp critique of how international legitimacy is often reserved for the powerful and denied to the small. His words challenge the assumption that indefinite leadership is inherently dictatorial and raise a fundamental question: Is dictatorship a system—or a label?

In many Western parliamentary democracies, long-serving leaders are not uncommon. Angela Merkel ruled Germany for 16 years. Canada’s Pierre Trudeau served for 15. No outrage. No sanctions. But when a developing country like El Salvador proposes similar continuity through elections, it is swiftly branded undemocratic.

Bukele’s frustration echoes the idea that “dictatorship is what states make of it.” That is, power structures—be they parliamentary, presidential, or otherwise—are not inherently authoritarian. Rather, the label of “dictator” is often applied based on who exercises the power and how the world perceives them.

Bukele doesn’t hide behind semantics. He admits the distinction between presidential and parliamentary systems but points out the inconsistency: “If El Salvador declared itself a parliamentary monarchy with the same rules as the UK… they still wouldn’t support it.” Why? Because sovereignty in the global order is conditional. Poor countries are expected to imitate, not innovate.

This narrative puts small states in a bind: govern like the West, or risk being labeled a threat to democracy. Bukele’s refusal to accept this binary is a radical assertion of national agency. It says that the rules of governance should not be dictated by wealth, geography, or geopolitical favoritism.

Under Bukele, El Salvador has pursued aggressive crime-fighting policies, infrastructure development, and political reforms—moves widely supported at home but viewed with skepticism abroad. While critics warn of democratic backsliding, supporters argue he has restored order in a once-volatile state.

What Bukele reveals is that “dictatorship” is not only about institutions—it’s about narrative control. Who tells the story, and who gets to define the terms? In this context, the tension is less about constitutional clauses and more about who is allowed to exercise strong leadership without international reprimand.

Rather than debating whether El Salvador’s political system mirrors liberal democracies, perhaps the more pressing question is: Why are small nations denied the same flexibility afforded to larger powers?

If democracy means sovereignty and self-determination, then Bukele’s El Salvador is asking for no more than what the global North already enjoys—the right to choose its own path.

President Bukele’s tweet isn’t just political commentary; it’s a challenge to the world order. It forces us to reconsider the meaning of dictatorship and the fairness of global norms. Ultimately, dictatorship may not be what a constitution says—it may be what the world decides to call it.

In other words, President Bukele’s statement encapsulates the core idea that dictatorship is not a fixed reality, but a label shaped by global power dynamics, national agency, and political storytelling.

In short, “dictatorship is what states make of it”—and what powerful actors let them make of it.

Bukele is not just defending indefinite reelection; he’s challenging the international system’s ability to impose meanings on domestic governance, asserting that a sovereign state must be allowed to define its own political path—even if that path resembles forms of power often tolerated in wealthier nations.

Credit: x.com.

Leave a Reply